Watching the Wires

How AI and Naval Vigilance Are Protecting Britain's Undersea Lifelines

A silent battle is unfolding beneath the waves, and it's time to recognise its significance. From the North Sea to the Baltic, an intricate network of vital undersea cables forms the backbone of our digital existence. These fibre-optic connections carry up to 99% of the world's internet traffic, linking financial markets, powering global communications, and underpinning defence systems. Yet, they face increasing threats.

Britain can no longer afford to ignore the vulnerabilities of this critical infrastructure. In response, we are deploying robust new tools—especially advanced AI surveillance systems and enhanced naval patrols—to safeguard what lies beneath. This transformation is not just about improving machinery; it's a crucial change in mindset that reflects our commitment to protecting our digital future. A silent battle is taking place beneath the waves. From the North Sea to the Baltic, a network of essential undersea cables forms the invisible framework of our digital lives. These fibre-optic lines carry up to 99% of the world's internet traffic, connecting financial markets, powering global communications, and supporting defence systems. Unfortunately, they are increasingly at risk.

Britain, which once overlooked the vulnerabilities of this critical infrastructure, is now implementing new measures—particularly AI surveillance systems and strengthened naval patrols—to monitor what lies beneath the surface. This shift is not only about upgrading technology but also transforming mindsets.

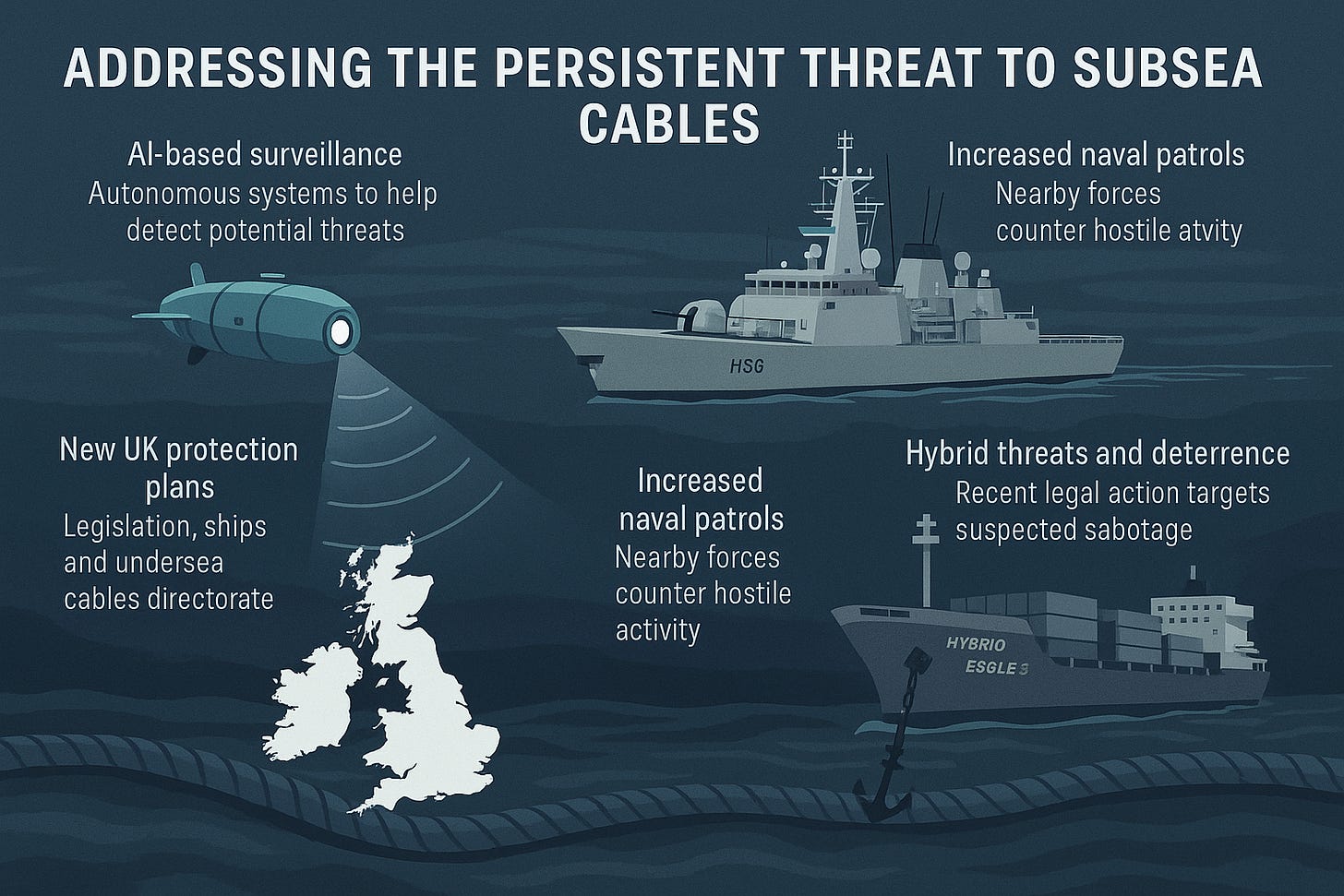

In January 2025, the UK Ministry of Defence, as part of a Joint Expeditionary Force, activated a UK-led reaction system to track threats to undersea infrastructure and monitor Russian shadow fleet operations. Nordic Warden is an AI-powered monitoring system developed in partnership with NATO allies and the analytics firm Palantir. The platform ingests real-time data from satellites, shipping lanes, sonar feeds, and undersea sensors to detect anomalies around critical seabed infrastructure. It tracks "dark" vessels with deactivated transponders, watches for patterns like slow loitering near cable routes, and flags anything from an anchor drag to a stealthy submersible.

Meanwhile, Royal Navy patrols have been increased dramatically. When the Russian spy ship Yantar loitered in the English Channel late last year, it was intercepted by HMS Somerset and tracked by the specialised RFA Proteus, the UK's new seabed surveillance ship. That was no accident. British officials are now openly calling out Russia's covert activity in these so-called "grey zones," deploying assets not just to respond, but to deter.

A Strategic Pivot: Laws, Plans and Patrols

This burst of activity marks a strategic pivot in UK policy. For years, undersea infrastructure was the domain of telecoms companies and largely ignored by national security planners. That changed after a flurry of Baltic sabotage incidents between 2022 and 2024, culminating in the arrest of the Russian-linked Eagle S tanker by Finnish authorities for its involvement in cable-cutting operations.

Parliament has since launched formal inquiries. Ministers now acknowledge that Britain's main cable protection law, the 1885 Submarine Telegraph Act, is outdated. A new Defence Readiness Bill, currently in development, will overhaul legal powers to protect critical subsea infrastructure. Complementary updates to the UK's cyber and infrastructure resilience laws are also underway, ensuring that supporting services to undersea infrastructure are included in resilience planning.

The Royal Navy has expanded its mission to include seabed protection. The RFA Proteus, the first of two dedicated surveillance ships, can deploy drones and submersibles to inspect cables and pipelines. RAF Poseidon aircraft now regularly fly over the North Sea and English Channel to track suspect vessels. Meanwhile, NATO's new Baltic Sentry mission, involving UK and allied ships, maintains a persistent presence in high-risk zones.

Even more critical is what experts call "resilience by design." The UK and allies are enhancing redundancy, training repair crews, securing landing stations, and hardening data centres. It's not just about preventing attacks — it's about recovering quickly when something goes wrong.

Meanwhile, Professor Jacques Hartmann of the University of Dundee points to a gaping legal loophole. There's no solid international framework for boarding vessels suspected of peacetime sabotage. His provocative proposal? Classify cable-cutting as piracy, making perpetrators liable to arrest on the high seas. A defining example of this new assertiveness emerged with the Eagle S case in late 2024. The crude-oil tanker, linked to Russia's shadow fleet and flying a Cook Islands flag, was accused of dragging its anchor across the seabed in the Gulf of Finland, severing the Estlink 2 power cable and damaging multiple telecom lines. Finnish authorities boarded the ship, discovered the missing anchor and drag marks, and detained the crew on suspicion of aggravated sabotage. Legal proceedings are ongoing, but the case marks a watershed moment: one of the first real-world examples of a nation-state detaining a commercial vessel on suspicion of interfering with undersea infrastructure. It has prompted renewed calls to redefine such acts as piracy under international law and shown that grey zone aggression at sea no longer guarantees impunity.

Why Now? Understanding the Threat

The real question isn't why the UK is acting, but why it waited so long. As Dr Katja Bego from Chatham House noted in a recent RUSI webinar, subsea cables have always been fragile. She calls their exploitation by states like Russia and China a clear case of the "weaponisation of undersea infrastructure."

But the strategic use of cable sabotage isn't new. Dr Sidharth Kaushal of RUSI highlighted that over 200 cables break each year, most of which are due to accidents. But in shallow seas like the Baltic or Irish Sea, hostile actors can easily mask sabotage as coincidence. "Temporal attacks," he warned, would likely surge during conflict, aiming to paralyse command systems just as war breaks out. He cited a case where a U.S. military cable failure temporarily grounded drone systems during Iran's missile strike on Al Asad Air Base in January 2020. Fires from the attack melted key fibre-optic cables used by U.S. forces to operate unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). As communications were severed, 14 drone pilots lost contact with their aircraft mid-flight, forcing emergency repair crews to replace over 500 metres of damaged cable before satellite links could be re-established. Each UAV had to be landed manually.

The incident highlighted how even terrestrial cable damage — in this case from fire rather than sabotage — can cripple drone operations, reinforcing the strategic importance of robust and resilient cable infrastructure in both warfighting and deterrence.

Dr Camino Kavanagh, a senior UN researcher and author of the UNIDIR report on undersea cables, goes further. She calls for expanded thinking. It's not just about cable routes — it's about landing stations, repair ships, control systems, and cyber hygiene. She warns that compromised software aboard cable-laying vessels could delay recovery or mask a hack as a hardware fault; the entire ecosystem must be considered.

The View Ahead: Watching the Unseen

Britain is now embracing this whole-system view. As Russian "research ships" quietly scan the seabed near UK waters and NATO cables, the UK is watching — and learning. Through AI, such as Nordic Warden, and through naval assets like Proteus, as well as legislative action, the UK is signalling that the ocean floor is no longer a lawless place.

And this vigilance is not just a national concern. The UK is leading coordination through NATO and the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF), ensuring that allies such as Sweden, Finland, and Norway are part of a unified deterrent. Even commercial operators — once hesitant — are now engaging with defence planners.

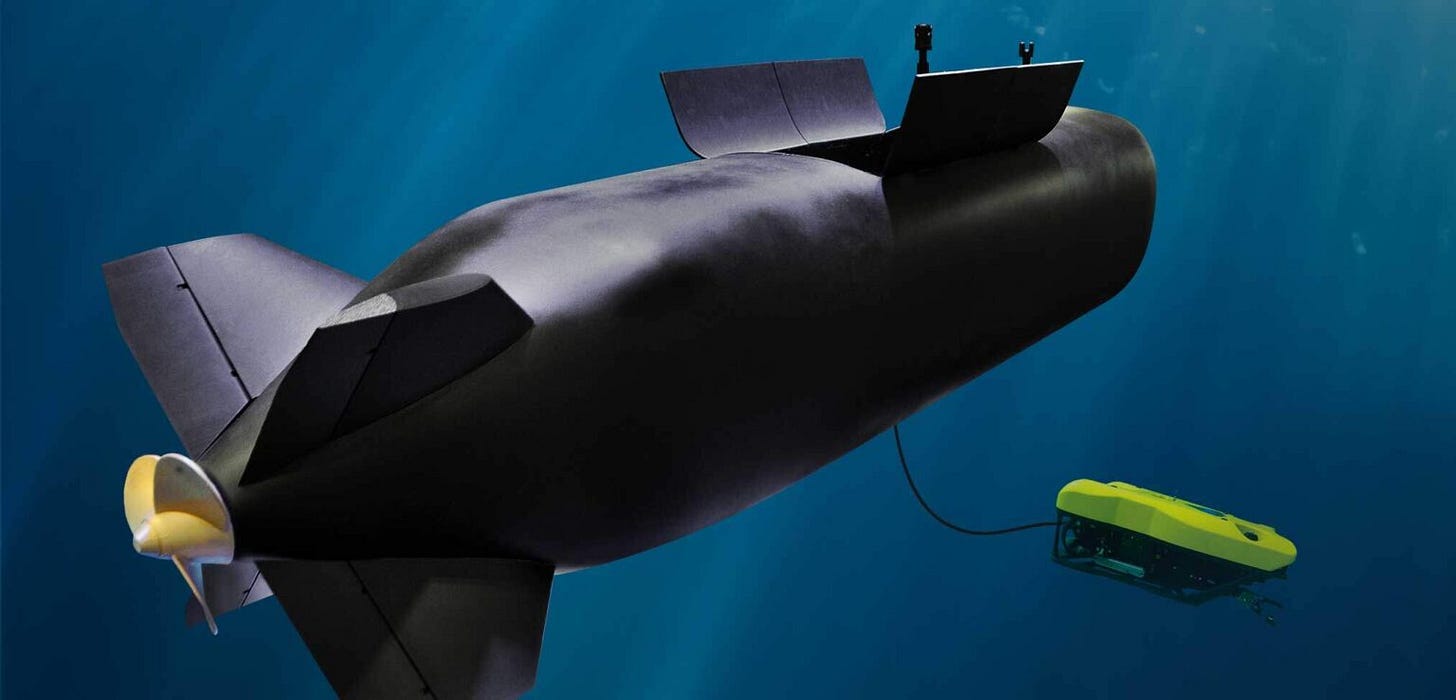

Looking ahead, the Royal Navy is expanding its toolkit beneath the waves through the introduction of unmanned and autonomous systems. Platforms like the CETUS XL-AUV — a next-generation extra-large autonomous underwater vehicle — are currently in advanced trials and signal a strategic shift in how the UK monitors and defends its subsea infrastructure. These systems are designed to operate at depth for extended periods, mapping the seabed, tracking anomalies, and responding to incidents far beyond the reach of traditional patrols. Paired with remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and AI-assisted surveillance networks, these unmanned assets provide a persistent undersea presence without requiring continuous human operation. While still in the early phases of operational integration, their role is clear: to safeguard the deep, deter hybrid threats, and help ensure that Britain's critical undersea lifelines remain secure in the years ahead.