The White Ensign in the Autonomy Era

Redefining Naval Support for the Age of Autonomy

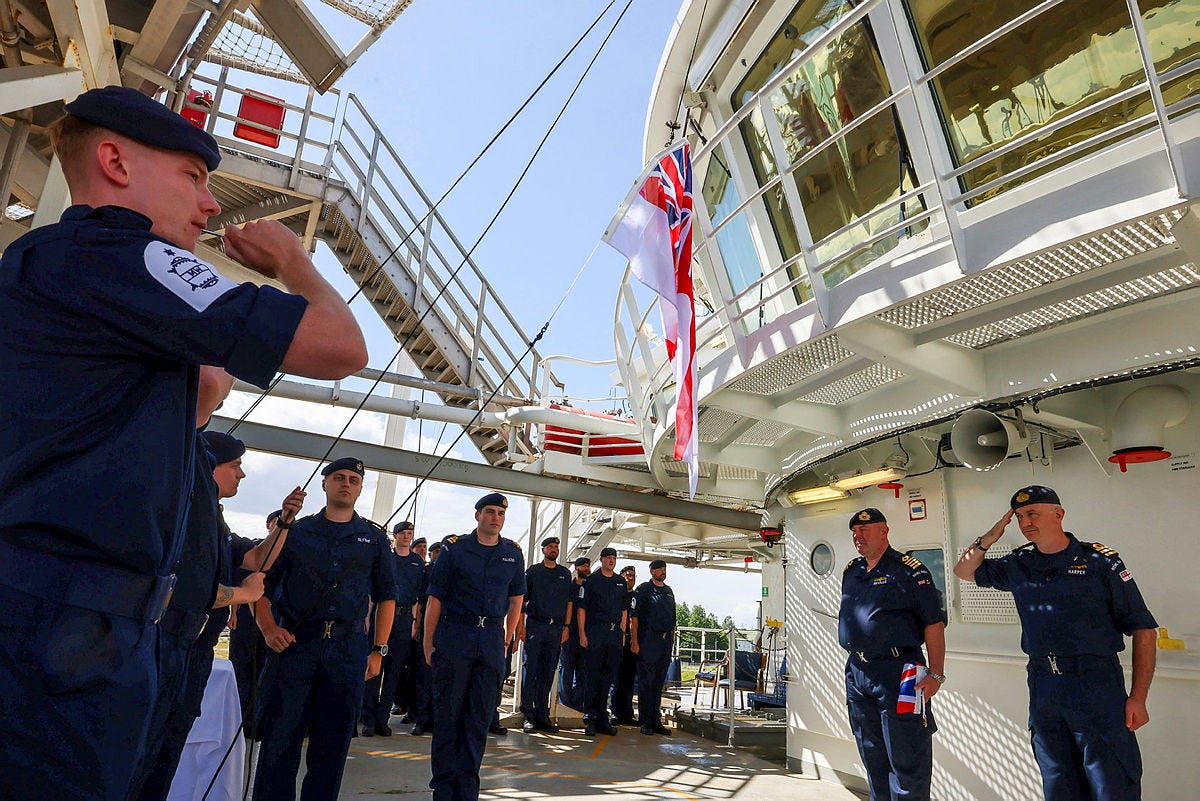

When HMS Stirling Castle hoisted the White Ensign in July 2025, it passed largely without public attention. Yet for those watching closely, it marked a quiet but profound shift. A vessel originally intended for the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) was absorbed into the Royal Navy (RN), not as a ceremonial gesture, but due to necessity. There were no available RFA crews, and operational timelines could not wait. The ship became a commissioned warship out of sheer practical demand.

In the current era of artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, and persistent maritime competition, the question of whether we can afford to persist with a 20th-century model for naval logistics is not just a theoretical one. It's a pressing issue that demands immediate attention and action.

A Legacy of Endurance: The RFA's Past Role

During the Cold War and the Falklands War, the RFA played a vital and often understated role. As someone who served during these times, I can attest to the critical support these vessels provided. They were not just support ships, but enablers of reach, resilience, and autonomy. Their indispensability was most evident during the South Atlantic conflict, where they carried the burden of sustainment across vast distances and under contested conditions, enabling us to reach and win the fight.

But today, the RFA's capacity is shrinking at an alarming rate. Ship numbers have fallen, replenishment at sea capability has eroded, and personnel shortages are acute. The current trajectory leaves the Royal Navy with ambitious global aims but limited endurance, demanding immediate attention and action.

New Threats, New Demands: Autonomy, AI and Naval Logistics

Naval warfare is evolving. The sea is now contested not only by traditional threats, but also by data-rich autonomous systems operating across surface, subsurface, and aerial domains. This evolution has profound implications for logistics. Support platforms must now manage more than fuel and food. They must sustain drone operations, manage AI model updates, distribute power cells, and serve as forward-deployed command nodes for uncrewed systems. Mission flexibility, cybersecurity, and digital sustainment are now baseline requirements.

In this environment, platforms like RFA Proteus and HMS Stirling Castle are not just enablers—they are strategic assets in their own right. The forthcoming Multi-Role Support Ships (MRSS) will need to deploy modular payloads, facilitate remote and autonomous systems, and operate in contested grey zones.

Support ships are no longer behind the fleet; they are part of it.

The Organisational Divide: A Growing Strategic Mismatch

The current division between RFA and RN was fit for a different era. Civilian-crewed ships brought efficiency and cost-effectiveness, with merchant service protocols enabling flexibility. But in today's operating environment, this is increasingly mismatched with strategic needs.

Personnel shortfalls in the RFA are leading to laid-up vessels, delayed trials, and lost operational tempo. A Royal Navy that fields fifth-generation combatants and operates in high-intensity theatres should not be dependent on under-crewed auxiliaries to remain deployable.

During recent deployments, the UK had to rely on a Norwegian support ship to resupply its carrier group—a stark indicator of vulnerability.

Naval Enablers as Core Combat Systems

The conversation must now shift. We must view our auxiliary fleet not as support, but as core combat infrastructure. These ships must be:

Fully integrated into digital command-and-control frameworks

Capable of operating autonomously or supporting uncrewed systems

Hardened against cyber threats

Designed for modularity and mission reconfiguration

Staffed with warfare specialists, engineers, software technicians, and UAV operators

This is not a speculative future—it is now a live operational requirement. The strategic importance of modernised naval enablers cannot be overstated, making the proposed reforms a matter of utmost significance.

Design innovation matters. BMT's newly expanded ELLIDA™ "FutureBMT " set design offers a compelling vision of what next-generation support vessels could look like. Unveiled at DSEI 2023 and refined from BMT's earlier AEGIR and Tide‑class designs, BMT's ELLIDA future prioritises reduced crewing, modular payloads, and automation, tailored explicitly for contested littoral environments and autonomous system support.

Notably, the second-generation design removes traditional RAS rigs in favour of large internal decks, a floodable well dock for landing craft or USVs, TEU‑container stowage zones, modular vehicle decks and containerised medical modules like a casualty-reception facility—all while maintaining efficient performance with crew complements below 70

This kind of platform aligns closely with the Future Navy vision: a ship that can simultaneously act as amphibious support, solids replenishment, drone mothership, and incident command node—operated by a lean, tech-empowered crew. However, there was no explicit endorsement of designs like ELLIDA within the 2025 Strategic Defence Review (SDR) text. The review did confirm commissioning of up to six Multi‑Role Strike Ships (formerly MRSS), intended to deploy drones, well docks, and modular payloads from the early 2030s. But while the opportunities opened here, and were aligned with ELLIDA principles, the SDR did not name or commit to specific designs.

Organisational Reform: Merger or Integration?

A full RFA–some commentators have suggested an RN merger. There is logic in it: harmonising pay, training, and personnel structures could reduce duplication and increase operational flexibility.

But such a move would also risk losing the commercial strengths and agility that the RFA offers.

An alternative approach is to establish a Naval Auxiliary Command (NAC):

A joint structure within the Royal Navy, responsible for both traditional logistics and new combat-adjacent enablers. It would:

Integrate RN and RFA command elements under a single star-level authority

Establish shared training and personnel development pathways

Enable the conditional commissioning of vessels into RN service based on the threat environment

House specialist teams for AI-enabled logistics, subsea operations, and drone sustainment

This model could preserve the RFA's flexibility while improving its assignment to operational needs.

Addressing the Personnel Challenge: Practical Measures

To enhance the RFA's capabilities amid acute manpower shortages, several immediate and mid-term steps should be implemented:

Hybrid Crewing: Allow RN personnel to rotate onto RFA platforms, and contract short-term civilian mariners for mission-critical billets.

Fast-Track Training: Accelerate pathways for high-demand roles like engineers and systems techs.

Reserve Mobilisation: Establish a Naval Logistic Reserve Cadre, drawing from merchant mariners and retired RN personnel.

Flexible Surge Contracts: Enable skilled mariners to join deployments without full-time commitments.

Modular Task Teams: Deploy mission-specific teams (e.g. UAV or cyber support) as detachments, reducing strain on core RFA crews.

These measures would buy critical time while deeper reform beds in.

Merger Implications: Effectiveness vs. Efficiency

A complete merger of the RFA and RN would yield operational and financial gains—but not without risk. Benefits might include:

Greater operational flexibility and resilience

Unified command and logistics planning

Reduced duplication in procurement and personnel systems

Yet risks persist:

Loss of RFA's neutral status and diplomatic RFAs in peacetime

Increased personnel costs as pay harmonisation takes effect

Cultural integration challenges between civil and military workforces

Hence, the phased development of a Naval Auxiliary Command offers a balanced path, one that enhances capability without forcing structural convergence prematurely.

From Fuel to Firmware: A Strategic Transition

The RFA once represented endurance through fuel and stores. In the 21st century, endurance also means software, data links, and autonomy support. Suppose we continue to treat our auxiliaries as secondary. In that case, we risk building a Royal Navy that appears capable—but lacks the backend infrastructure to persist, adapt, or dominate in prolonged operations.

This is a critical inflection point. As the Future Navy evolves, so too must its enablers. Whether they fly the blue or white ensign, the ships that keep us in the fight must be modern, flexible, and integrated from keel to cloud.

In the Future Navy, the enabler is the weapon.