Future Navy: Mogami Lessons for the UK’s Maritime Future

Australia to buy eleven Japanese frigates

Introduction

Australia’s decision to acquire an upgraded variant of Japan’s Mogami-class frigate marks a watershed moment in naval cooperation and warship design. It is Japan’s first major warship export since the Second World War. It brings forward a set of design philosophies that align directly with the Royal Navy’s own Vision 2040 and Future Air Dominance System (FADS) discussions showcased at CNE 2025.

For Future Navy thinking, the Mogami purchase is more than an Australian story; it offers useful markers for how the Royal Navy might shape lean crewing, training, power growth, and uncrewed integration in the years ahead.

What the Mogami Brings

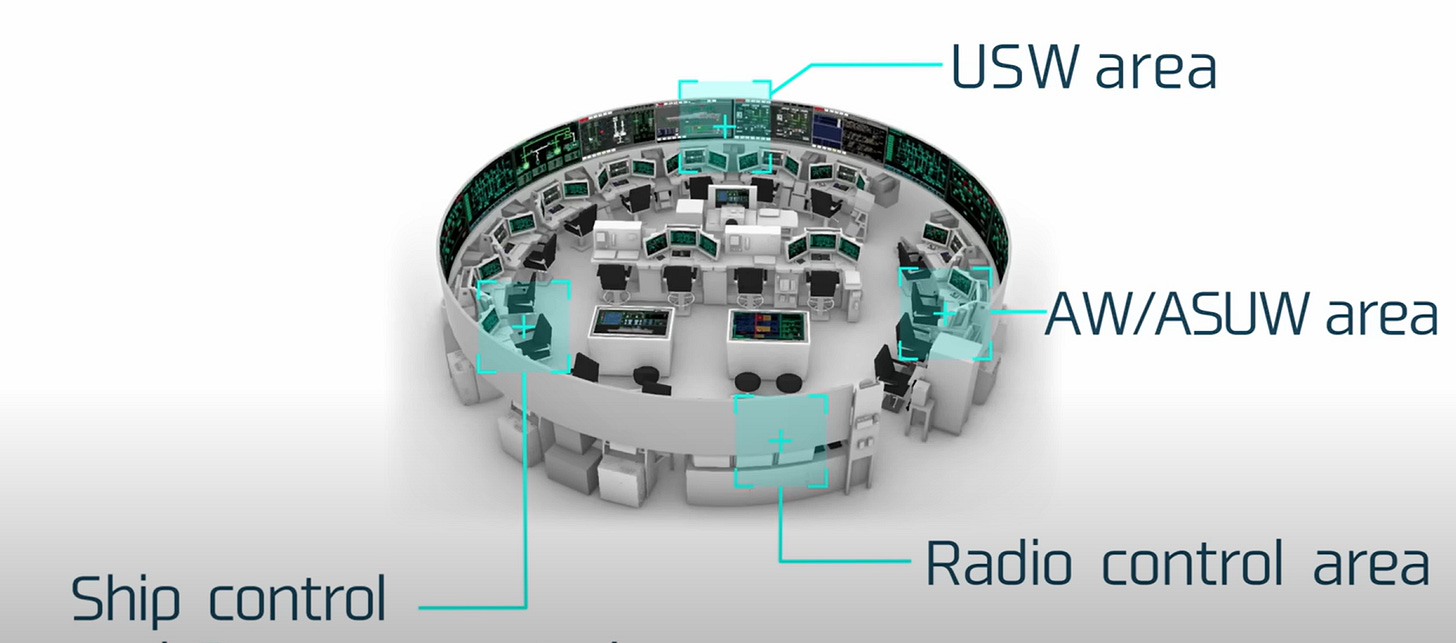

Lean Manning with a Modern CIC: The Mogami operates with around 90 personnel, and can surge down to 60 during combat. This is enabled by a 360° screen-wall CIC that absorbs communications and damage control functions, a radical step compared to UK practice.

Mission Flexibility: A stern mission bay, 20-foot access hatches, and built-in USV/UUV handling give the class a containerised, modular capability from day one.

Stealth and Survivability: With distributed exhausts and stealth shaping informed by aviation design, the Mogami reduces both radar and infrared signatures.

Future-Proof Power: Enlarged generators and increased space margins anticipate directed-energy and counter-drone weapons, a forward step many navies are still planning for.

Missile Capacity: With 32 Mk41 cells (allowing up to 128 ESSMs), the Australian variant offers a depth of magazine suitable for Indo-Pacific contested environments.

The Royal Navy’s Lean-Manning Challenge on Type 31

The Type 31 frigate was conceived as a low-cost, general-purpose platform with a core crew of about 105, a stark reduction from the ~180 on Type 23 frigates. The goal is to cut through-life costs and leverage automation. Yet this creates a series of operational challenges:

Dual Roles in Combat and Damage Control

The same sailors who manage weapons handling and magazine resupply will also be expected to fight fires and floods. In combat, these demands can clash.

Limited Redundancy in Command and Control

Type 31 carries a single operations room. If it is disabled, fighting capability is largely lost. Survivability through redundancy is weaker than in larger-manned ships.

Fatigue and Watchkeeping Burden

Smaller crews cover the same watches, meaning higher strain during long deployments. Automation helps but does not replace human situational awareness.

Training and Retention

With fewer billets, opportunities for junior training at sea are reduced, so the burden shifts to shore-based simulation and digital twin systems.

Wartime Reality

Survivability under heavy damage requires simultaneous firefighting, casualty handling, and rearming. With only ~100 personnel, the risk of being overwhelmed is real.

The Mogami contrast is instructive. Japan’s design integrates lean manning from the keel up, embedding automation, simulation, and a CIC concept that collapses functions by design. Type 31 is more of a compromise, seeking to do more with fewer sailors but within a relatively traditional structure.

Royal Navy Vision 2040 and FADS Connections

At CNE 2025, Vice Admiral Paul Marshall and Commodore Michael Wood highlighted key trajectories for the Royal Navy:

“Crewed where needed, uncrewed where possible”, the Mogami’s mine warfare USV/UUV capability shows precisely how to embed this principle from the keel up.

Digital training loops — JMSDF plans heavy reliance on shore-based simulation to prepare small crews; the RN has already signalled digital twin training as a growth area.

Directed-Energy Weapons (DEW) — both the Mogami upgrade and the RN’s FADS roadmap stress increased onboard power as a prerequisite.

Networked Defence — FADS envisions loyal-wingman USVs and missile barges; Mogami already provides a mission bay and integrated communications mast as a testbed for this philosophy.

Why This Matters for the UK

Lean Manning and Survivability

The Mogami takes lean manning to its logical end. But by collapsing CIC, comms, and damage control into one space, it raises survivability questions. For the RN, the lesson is to balance automation gains with redundancy.

Training Investment

Like Japan, the RN cannot afford to crew new ships with traditional watchkeepers. Digital twins and synthetic environments must become part of the ship’s lifecycle, not a bolt-on.

Industrial Lessons

Australia’s approach, buying three ships off a hot Japanese line, then shifting to local build, contrasts with UK practice of all-domestic build. It raises questions on whether greater industrial pragmatism could reduce delivery risk.

Power First

Mogami’s increased generators mirror the RN’s push to prepare for directed-energy weapons. Britain’s Type 31 and Type 26 designs should be benchmarked against this philosophy: “power before payload.”

A Positive Path Forward

The Mogami decision underlines a broader shift: navies that embrace automation, modularity, and energy growth will be better placed to counter drone swarms, long-range precision strikes, and grey-zone threats.

For the Royal Navy, Vision 2040 and FADS provide the strategic frame. The Mogami offers a real-world, allied example of how those ideas can be translated into steel.

The opportunity is to learn fast, adapt intelligently, and ensure the UK fleet is not just relevant but credible, interoperable, and resilient through the 2030s and beyond.

Closing Thought

In the words of Vice Admiral Duncan Potts at CNE 2025: “Control of the sea and denial of it to others is fundamental in an uncertain world.” The Mogami purchase shows how one ally is reshaping that control. For the UK, it is a call to turn concepts into capabilities with urgency, confidence, and vision.