2025 in Review: How the Royal Navy Entered a Pre-War Era — and What 2026 Must Deliver

The Emergence of the Future Navy and the Imperatives for 2026

Introduction: The Year Time Ran Out

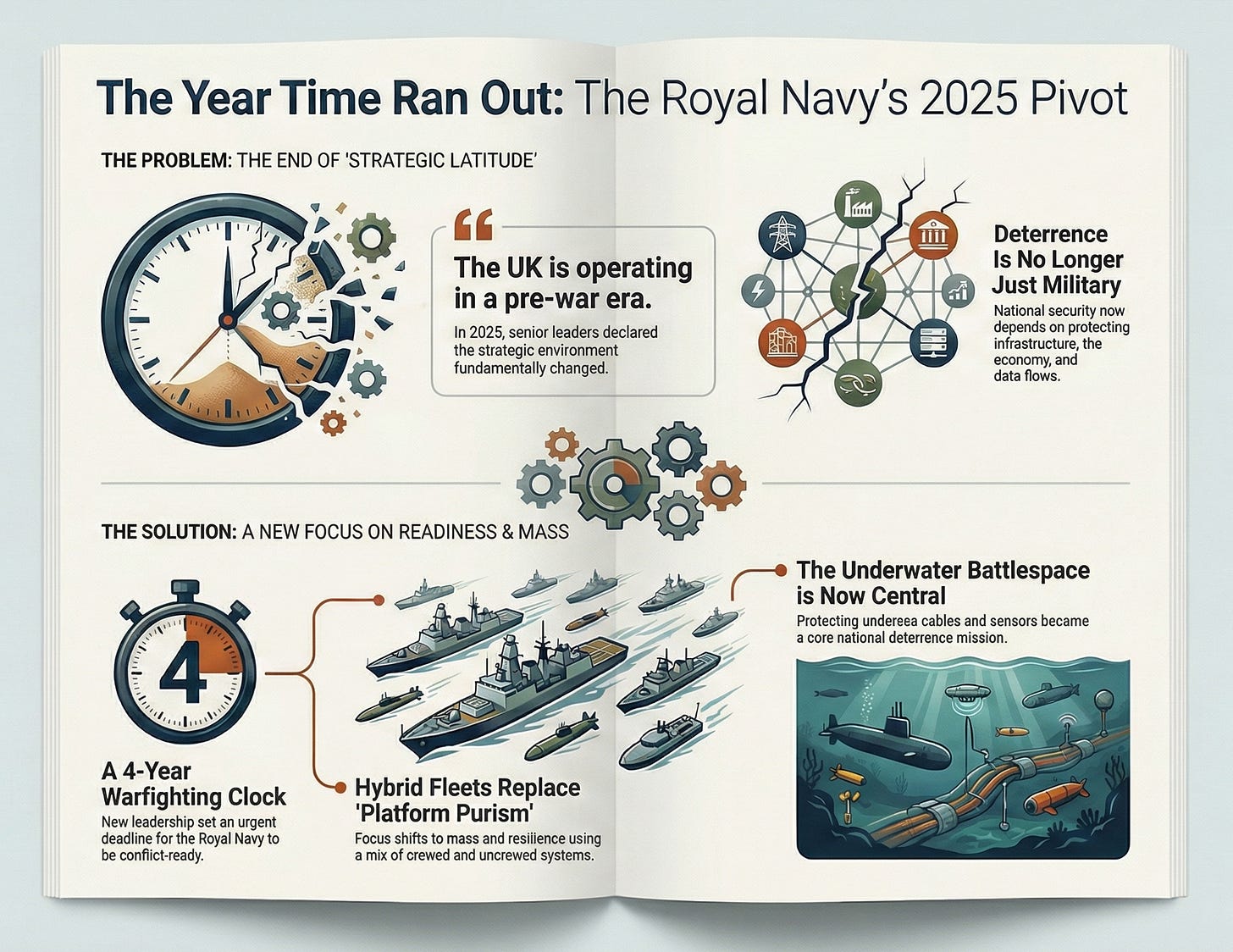

2025 will be remembered not for the Royal Navy defining its future, but for acknowledging the end of its strategic latitude.

Throughout the year, decisions previously scheduled for the 2030s were accelerated by geopolitical pressures, industrial constraints, and an increasing awareness that deterrence is no longer guaranteed. By December, this understanding became explicit: senior defence leaders now describe the UK as operating in a pre-war era.

This shift represented substantive and structural change, not merely rhetorical adjustment.

Throughout 2025, Future Navy documented this transition, highlighting the vulnerability of undersea cables and the Atlantic Bastion, the operational necessity of autonomy and artificial intelligence, and the requirement that a carrier represents true capability only when deployed with a credible supporting group.

By year’s end, the trajectory was clear and irreversible.

A New First Sea Lord — And a Change of Tempo

Prior to the strategic focus expanding to encompass society, industry, and national resilience, the most immediate shift in 2025 originated within the Royal Navy.

In May 2025, General Sir Gwyn Jenkins KCB OBE ADC RM became the First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff — the first Royal Marine ever to hold the role.

Sir Gwyn commissioned into the Royal Marines in 1990, serving early in the Commando Logistics Regiment and on operations in Northern Ireland with 42 Commando. His formative years were spent not in large platform commands but in expeditionary, resource-constrained environments where adaptability, tempo, and logistics determined success or failure.

His operational background is reflected in his leadership approach.

From his initial public statements as First Sea Lord, his language has been operationally focused, prioritising time, readiness, and the realities of warfighting over abstraction or caution. In contrast to previous naval leadership, which often discussed transformation programmes and future pathways, Sir Gwyn emphasised concrete deadlines.

His most notable intervention was a direct assessment that the Royal Navy has four years to achieve operational readiness for conflict.

This framing is substantive, condensing decades of ambition into a single planning horizon and indicating a leadership style focused on tangible outcomes rather than process. It also reflects a willingness to confront difficult realities, including shortfalls in escorts, fragile availability, and the gap between conceptual capability and deployable force at scale.

Equally significant is his approach to change. Sir Gwyn demonstrates little tolerance for platform purism or traditional prestige. Instead, he consistently emphasises mass, persistence, and adaptability, recognising that in a missile-dense, data-rich battlespace, survivability depends as much on numbers and networks as on individual platforms.

His openness to autonomous escorts, hybrid fleets, and rapid expansion of uncrewed systems reflects a Royal Marine perspective shaped by operational experience rather than acquisition cycles. In this context, autonomy is regarded as a means to restore tempo, resilience, and operational depth, rather than as a technological experiment.

As Chairman of the Navy Board, Sir Gwyn is responsible for the fighting effectiveness, efficiency, and morale of the Naval Service. In practice, his first year in the role has established a clear direction: transformation is now a matter of urgency rather than a distant aspiration.

Subsequently, the Chief of the Defence Staff broadened the focus to include whole-of-society deterrence. NATO formalised the Digital Ocean initiative, and the industry advanced new autonomy partnerships. However, the initial momentum and urgency originated within the Royal Navy.

Although the Royal Navy has increased recruitment, this influx has not yet reversed the decline in overall trained strength. New recruits remain in training for extended periods before becoming operationally deployable, so they do not immediately offset the loss of experienced personnel. As a result, the service continues to experience a net deficit in skilled manpower, with qualified personnel leaving faster than they can be replaced. In 2025, the Royal Navy shifted from viewing transformation as a future concept to treating it as an immediate operational deadline.

From Assumption to Urgency: The Strategic Mood of 2025

The defining feature of 2025 was not a particular platform, announcement, or programme, but a fundamental change in strategic tone.

Operationally, the Royal Navy shifted from incremental modernisation to explicit warfighting readiness. Nationally, the conversation moved from abstract risk to tangible vulnerability, focusing on energy systems, data flows, ports, and seabed infrastructure.

This convergence was significant, reframing naval power from a focus on ships and submarines to its role within a broader system supporting national security and daily life.

This reframing was articulated most clearly in December at RUSI. In his annual address, the Chief of the Defence Staff set the clearest strategic context of the year. He described the current environment as more dangerous than at any point in his career and argued that while deterrence has so far held, the trend line is worsening and the cost of failure rising.

He emphasised that deterrence is not solely a military function, but a whole-of-society responsibility. While the armed forces remain the first line of defence, future conflicts are equally likely to target infrastructure, the economy, and public resilience as to occur on distant battlefields.

This was not a theoretical abstraction. The Chief of the Defence Staff explicitly referenced cyber attacks, undersea infrastructure, industrial capacity, and skills as decisive factors in contemporary deterrence. The implication is clear: security cannot be delegated solely to the military.

In doing so, the Chief of the Defence Staff provided national validation for themes that had emerged in Royal Navy discourse throughout the year, particularly the centrality of the Atlantic, the seabed, and the systems sustaining the UK’s economy and alliances.

If 2025 marked the year the underwater battlespace became central to NATO planning, it also marked the transition of the Atlantic Bastion from a naval discussion point to a matter of national concern.

NATO’s decision to establish a common Allied Underwater Battlespace Mission Network marked a decisive shift, recognising that future maritime competition will be determined by networks, data, and interoperability rather than hull numbers. The UK’s leadership in this effort positions the Royal Navy at the centre of the emerging Digital Ocean architecture.

The Chief of the Defence Staff’s December remarks reinforced this perspective, warning that attacks on infrastructure and the economy are central elements of contemporary conflict, not secondary risks.

In this context, protecting undersea cables, seabed sensors, ports, and maritime data flows is now a core component of national deterrence, rather than solely an anti-submarine warfare task.

Hybrid Fleets and the End of Platform Purism

Operationally, 2025 marked a decisive shift away from platform-centric thinking.

The First Sea Lord’s guidance was explicit: future warfighting will depend on hybrid fleets integrating crewed platforms with autonomous surface, subsurface, and airborne systems. The objective is mass, persistence, and survivability, not novelty.

The Chief of the Defence Staff reinforced this logic in December, describing transformation as a high–low mix delivered rapidly, blending advanced capabilities with affordable, scalable systems that can be quickly adapted.

This framing is significant, signalling institutional recognition that the era of highly specialised, scarce platforms operating independently has ended. The future fleet will be evaluated by its integration of personnel, data, autonomy, and industrial scale.

Shared Infrastructure and the Quiet Enabler of Change

One of the most consequential yet least visible developments in 2025 was the maturation of the Royal Navy’s Shared Infrastructure approach.

By consolidating numerous combat systems into a unified digital environment, Shared Infrastructure has become the foundation for future ambitions, including AI-assisted decision-making, rapid software updates, leaner manning, and integration of uncrewed systems as the backbone. The hybrid fleet remains aspirational, but with Shared Infrastructure, autonomy, and AI, it becomes operationally plausible.

This development marks the point at which the Navy’s transformation becomes credible rather than conceptual.

Type 31: From Budget Frigate to System Host

Few debates in 2025 evolved as significantly as the discussion regarding the Type 31 Frigate.

By year’s end, the central question shifted from whether the Type 31 was ‘good enough’ to whether the Royal Navy could afford not to leverage the only surface combatant explicitly designed for modularity, open systems, and autonomy integration.

The Chief of the Defence Staff’s emphasis on scale, affordability, and adaptation speed implicitly strengthens the case for the Type 31. Although not named directly, the platform fits the described role: a system host capable of carrying uncrewed mass, evolving digitally, and operating as part of a wider networked force.

In a fleet constrained by the number of available escorts, this consideration is especially significant.

AI, Command, and the Human Factor

Throughout 2025, artificial intelligence shifted from a subject of speculative discussion to an operational necessity, accompanied by greater realism regarding its limitations.

Both the Chief of the Defence Staff’s address and subsequent discussions emphasised that artificial intelligence must be integrated into combat systems without undermining command responsibility or trust. The primary challenge is to streamline staff work, accelerate decision-making, and reduce cognitive burden, rather than to replace commanders.

The Chief of the Defence Staff directly linked technological transformation to personnel and organisational culture, emphasising that retention, leadership, skills, and training remain decisive. Artificial intelligence without trust is fragile, and autonomy without assurance poses significant risks.

This balanced perspective aligns with the Royal Navy’s current direction and the findings of comprehensive analytical work across Defence.

A recurring reality in 2025 was that a carrier does not constitute true capability unless deployed with a credible supporting group.

Escort availability, maintenance cycles, and sustainability have become immediate operational constraints rather than abstract planning concerns. The year saw renewed public debate over fleet size, readiness, and the risk of diminished capability from overcommitment.

The Chief of the Defence Staff addressed this reality, arguing that readiness includes stockpiles, training, personnel, and the capacity to engage in conflict immediately, rather than at an unspecified future date.

In 2026, this tension will either intensify or begin to resolve.

2026: From Direction to Proof

By December 2025, the strategic picture had become clear.

The First Sea Lord had set a four-year warfighting clock.

The CDS had framed deterrence as national, not merely military.

The Atlantic and underwater domains had become central theatres.

Consequently, 2026 will test these ambitions.

The focus will shift from new strategies or rhetoric to demonstrable outcomes.

Five tests will matter most:

Can the Royal Navy deploy a credible hybrid task group, not an experiment?

Do uncrewed systems move from trials to routine tasking?

Is the Atlantic Bastion defended as a system rather than just patrolled?

Does Type 31 begin to absorb autonomy at scale?

Is AI visible in operations rooms without breaking command culture?

These objectives are not abstract ambitions; they represent concrete tests of delivery.

Conclusion: A Navy Re-Entering History

2025 marked the year the Royal Navy shifted from analysis to action.

By year’s end, both naval and national leadership were aligned on a fundamental principle: deterrence now relies on readiness, resilience, and the capacity to adapt more rapidly than adversaries. While ships remain important, networks, personnel, data, and industrial capacity are equally critical.

The future fleet has moved beyond the conceptual stage and is now being assembled under significant pressure, in public view, and within a constrained timeframe.